On the afternoon of February 11, the Tehran Radio made a historic statement: “This is the voice of Iran, the voice of true Iran, the voice of the Islamic Revolution.” The loud voices of millions of Iranians silenced the 53-year-old dynasty and the 2,500-year-old monarchy. Their revolution became a watershed event that heralded the return of religious revolution to the annals of modern history. This was the beginning of radical changes in Iran’s domestic and foreign policy. In the international system, the Iran factor was evolving into a new dimension and this had important consequences both in terms of the Middle East and of Islam-West relations.

The rapid collapse of a mighty autocratic regime, the use of religion as the primary instrument of political mobilization, the tremendous level of animosity displaced against the West, and the establishment of a theocracy in the later decades of the twentieth century offered serious and difficult consequences.[1] This revolution had many peculiarities but the most obvious one was that it was the first contemporary revolution that has led to the establishment of a theocracy, while all other modern revolutions were against the state and church.

Iran thus became the first modern state to adopt an Islamic ideology and proved an inspiration to Islamist movements across the Middle East, Central, and South-East Asia.[2] The revolution helped inaugurate a wave of religious political activism in the Muslim world that has been referred to as Islamic fundamentalism, Islamic militancy, or Islamic radicalism.[3] Although the revival of Islamic fundamentalism can be traced back to the 1920s, and particularly the founding of the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt in 1928, its most significant developments came in during and after the Iranian Revolution.[4]

There has been much speculation on whether the revolution could have been prevented if only this or that had been done. According to Ervand Abrahamian, such speculation, however, is as meaningless as to whether the Titanic would have sunk if the deckchairs had been arranged differently. The revolution erupted not because of this or that last-minute political mistake. It erupted like a volcano because of the overwhelming pressures that had built up over the decades deep in the bowels of Iranian society. The shah was sitting on such a volcano, having alienated almost every sector of society.[5

Despite all its peculiarities, the 1979 Revolution was a classical case of how rulers that are isolated from their people and ignore their needs will fall soon or later. So, to be able to understand what made Iranians so displeased that it ended up with such a revolution, one should go back in time to take a look at the Pahlavi rule with all its flaws.

In 1921, a military officer named Reza Khan seized power and four years later abolished the weakened Qajar dynasty and declared himself the Shah of a new Pahlavi Dynasty. Reza Shah managed to create a centralized bureaucratic state by modernizing the economy and secularizing political life.[6] Reza Shah came to power in a country where the government had little presence outside the capital. He left the country with an extensive state structure – the first in Iran after two thousand years. It has been said of Stalin that he inherited a country with a wooden plough and left it with the atomic bomb. It can be said of Reza Shah that he took over a country with a ramshackle administration and left it with a highly centralized state.[7]

He was forced to abdicate his throne in 1941, however, because of his pro-German sympathies during World War II. He was deposed during the Anglo-Soviet invasion of Iran on 16 September 1941. After his abdication, the Allied Forces recognized his son Mohammad Reza Pahlavi as the new monarch when he was only twenty-two years old.

The new Shah had an easygoing character, unlike his father which could be useful for the Westerners while getting more influence on such a strategically placed oil-rich country. Mohammad Reza Shah, continued his father’s policy of authoritarian modernization while being extremely pro-Western in his foreign policy but his rule was not as strong as that of his father. Also, his closeness to foreign powers always made Iranians question his legitimacy.

He had a disagreement with his very popular nationalist Prime Minister Mohammad Mosaddeq which then forced him to leave Iran in 1953. Mosaddeq nationalized Iran’s lucrative oil industry in 1951, backing by the power of the opposition which was increased by the economic problems stemming from the Second World War.

Iranians were displeased from the fact that the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, -which today has turned into BP- placed in Abadan and operated there almost independently from the Iranian government, making very high profits from the country’s oil revenues. Most Iranians who worked in the oil fields in Abadan lived in squalor while the British lived in privilege. Words of Parviz Mina, a former employee of Anglo-Iranian Oil Company, shows clearly the humiliation of the local people: “There was a famous club in Abadan which the British staff used and there was a sign outside that club which said dogs and Iranians are not allowed”[8]

During the nationalist interregnum of Mosaddeq, land reform was on his agenda as well as the nationalization of oil revenues but a few months after his seizure of power, Mohammad Reza Shah, with the help of the British and the US intelligence services, overthrew Mosaddeq and returned to power. Iran’s very popular modern-day hero was silenced. But although Mossadeq was overthrown and his nationalization attempt failed, Iran’s share of oil revenues rose from about 20 percent to fifty percent. This can be taken as an example of how sometimes riots fail, but they can still make a difference. Rebellions cause bigger rebellions as long as the problems they originate from are not solved, as will be seen in the fate of Mohammad Reza Shah. Because although he came to power again, with the help of the US and Britain, this didn’t mean he regained the legitimacy he lost in the eyes of the public.

As the Shah forged closer ties with Western governments, anti-American sentiments increased and the opposition to his rule intensified over the years. In an age of republicanism, he flaunted monarchism, shahism, and Pahlavism. In an age of nationalism and anti-imperialism, he came to power as a direct result of the CIA–MI6 overthrow of Mossadeq – the idol of Iranian nationalism. In an age of neutralism, he mocked non-alignment and Third Worldism. Instead, he appointed himself America’s policeman in the Persian Gulf, and openly sided with the USA on such sensitive issues as Palestine and Vietnam.[9]

While decisions were being made with the full effect of foreign politicians, Shah seemed to be more concerned with cultivating an extravagant lifestyle than with running the country. He and his family were frequently pictured in the company with some of the World’s most influential people. Often hosting parties of spectacular opulence. [10]

Determined to make Iran into a Middle Eastern version of Japan, the Shah started his so-called White Revolution of 1963 in such a displeased environment. His reforms included plans like nationalization of forests, village education, women’s right to vote, further industrialization and modernization etc. The centerpiece of the reform package was a land reform that transferred capital and the regime’s support base from rural landowners to the urban bourgeoisie.[11] Taking a feudal economy and turning it into a capitalist modern economy was not well received by all in Iran, however.

It wiped out in one stroke the class that in the past had provided the key support for the monarchy in general and the Pahlavi regime in particular: the landed class of tribal chiefs and rural notables. His failure to follow up the White Revolution with needed rural services left the new class of medium-sized landowners high and dry. Consequently, the one class that should have supported the regime in its days of trouble stood on the sidelines watching the grand debacle.[12]

With industrialization, migration from rural areas to the cities increased, production in agriculture decreased, food items were being imported. By 1978, production-consumption social balances in Iranian society were completely disrupted. Tehran’s population grew from one million to five million, and now half of Iran’s population was urban but most of them were poor.

Aiming to undercut the public importance of Islam -which he regarded as a backward influence- the Shah cultivated both a Western image that many conservative Iranians found offensive and pre-Islamic versions of Iranian identity that centered on nationalism rather than religion.[13] So, the Shah’s reform package clearly eroded the influence of landowners and the clergy. This alone was enough for strong opposition to him. Many clerics were outraged. One religious scholar was particularly critical insisting that the white revolution was aimed at bolstering foreign interests in Iran and further eroding its sheer traditions. Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini in exile said that the only white thing about this white revolution was the influence of the white house. Ervand Abrahamian accepts the influence of the White Revolution on making the Khomeini movement triggered but according to him, there was a more important thing: The Shah gave extraterritorial rights in 1963 to American military officials.

All these reforms opened up an economic and cultural chasm between the two Irans. On one side stood the Shah and the upper-middle class of liberal technocrats and on the other side, the tradition-minded lower classes and clergy. The polarization between the regime and the clergy was an especially volatile situation. It meant that Iran had two rival elites, each of which saw the other as illegitimate.

What is more, many saw the formation of the Resurgence Party in 1975 and the closing of all other political parties by the Shah as an open declaration of war on the traditional middle class – especially on the bazaars and their closely allied clergy. It pushed even the quietist and apolitical clergy into the arms of the most vocal and active opponent – namely Khomeini.

The opposition continued its activities abroad. An article entitled “Fifty Years of Treason” written by Abul-Hassan Bani-Sadr, the future President of the Islamic Republic was published in Paris during his exile. It indicted the regime on fifty separate counts of political, economic, cultural, and social wrongdoings. “These fifty years,” the article exclaimed, “contain fifty counts of treason.”[14]

In 1977, the Shah’s loosening of the tight restraints, under the pressure of Western media, human rights organizations, and especially the Carter administration, gave the domestic opposition the opportunity to raise their voice.The opposition was based on three key elements: Conservatives, namely religious leaders and Ayatollahs, leftist groups, and the national front, which advocated the restriction of the Shah’s powers.[15]

Conservatives led by the Ayatollahs represented the strongest opposition. One of the two most important leaders of them, Khomeini, was forced to go from Iraq to Paris in 1978 during his exile, and Ayatollah Shariatmedari lived in the city Qom. The clergy, whose number reached 180,000, the large mass of people, and most importantly, the important capitalists of Iran, namely the Bazaris supported the conservatives.[16]

Compared with the other groups, the clergy had a set of advantages: a solid, centralized and hierarchical internal structure, strong communication networks, capable orators and liturgists, wide mobilizing networks (mosques, seminaries, Islamic associations, religious foundations, populist slogans, financial independence from the state, and not least the credibility that came from decades of opposition to the Shah. The clerics, in other words, fulfilled the functions of the Leninist vanguard party even if such a party did not actually exist.[17]

In this atmosphere of unrest, heavy criticism of the regime by well-known writers who met at ten poetry-reading evenings in October, and, the clashes between the police and the overflowing audience of them on the final evening was like fueling the fire. It was rumored that one student was killed, seventy were injured, and more than one hundred were arrested. These protests persisted in the following months, especially on December 7 – the unofficial student day.

In January 1978, the pro-government newspaper Ettela’at seemed to throw an anger bomb on the opposition. It ran an editorial criticizing Khomeini in particular and the clergy in general as “black reactionaries” in cahoots with feudalism, imperialism, and, of course, communism. On the following two days, seminary students in Qom took to the streets, persuading local bazaars to close down, seeking the support of senior clerics – especially Grand Ayatollah Shariatmadari – and eventually marching to the police station where they clashed with the authorities. In the aftermath of the clash, the regime claimed that the seminary students had been protesting the anniversary of Reza Shah’s unveiling of women. In fact, petitions drawn up by seminaries did not mention any such anniversary.

The Qom incident triggered a cycle of three major forty-day crises – each more serious than the previous one. The first – in mid-February – led to violent clashes in many cities. The second – in late March – caused considerable property damage in Yazd and Isfahan. The shah had to cancel a foreign trip and take personal control of the anti-riot police. The third – in May – shook twenty-four towns.[18]

For much of the first half of 1978, European diplomats argued that the periodic disturbances were a consequence of the Shah’s reforms. Few could realize that it was not a crisis of the state but a profound crisis of confidence by a monarch who simply could not reconcile the protests with his self-proclaimed image of a shah loved by his people. By the autumn it was apparent to the more astute that Iran was facing a fully edged revolutionary upheaval.[19]

Tensions were further heightened by two additional and separate incidents of bloodshed. On August 19 – the anniversary of the 1953 coup – a large cinema in the working-class district of Abadan went up in flames, incinerating more than 400 women and children. The public automatically blamed the local police chief, who, in his previous assignment, had ordered the January shooting in Qom. But in reality, this bloody event was the sign of how far the pro-Khomeinists were prepared to go to achieve their ideological ambitions because it was they who set fire to the cinema.

After a mass burial outside the city, some 10,000 relatives and friends marched into Abadan shouting “Burn the shah, End the Pahlavis. So, it seemed like a plan of the Khomeinists worked very well.

The second bloodletting came on September 8 – immediately after the shah had declared martial law. Commandoes surrounded a crowd in Jaleh Square in downtown Tehran, ordered them to disband, and, when they refused to do so, shot indiscriminately. September 8 became known as Black Friday – reminiscent of Bloody Sunday in the Russian Revolution of 1905–06. Black Friday and the Abadan fire are two very important events that made the gap between the Shah and the people widen so much that it could no longer be closed.

On December 11, 1978, the opposition negotiated with the government on behalf of Khomeini and reached a compromise on some issues. The government agreed to keep the military out of sight and confined mostly to the northern wealthy parts of the city. The opposition agreed to march along prescribed routes and not raise slogans directly attacking the personality of the shah.

On the Ashura day, four orderly processions converged on the expansive Shahyad Square in western Tehran. Foreign correspondents estimated the crowd to be in excess of two million. The rally ratified by clapping resolutions calling for the establishment of an Islamic Republic, the return of Khomeini, the expulsion of the imperial powers, and the implementation of social justice for the “deprived masses”

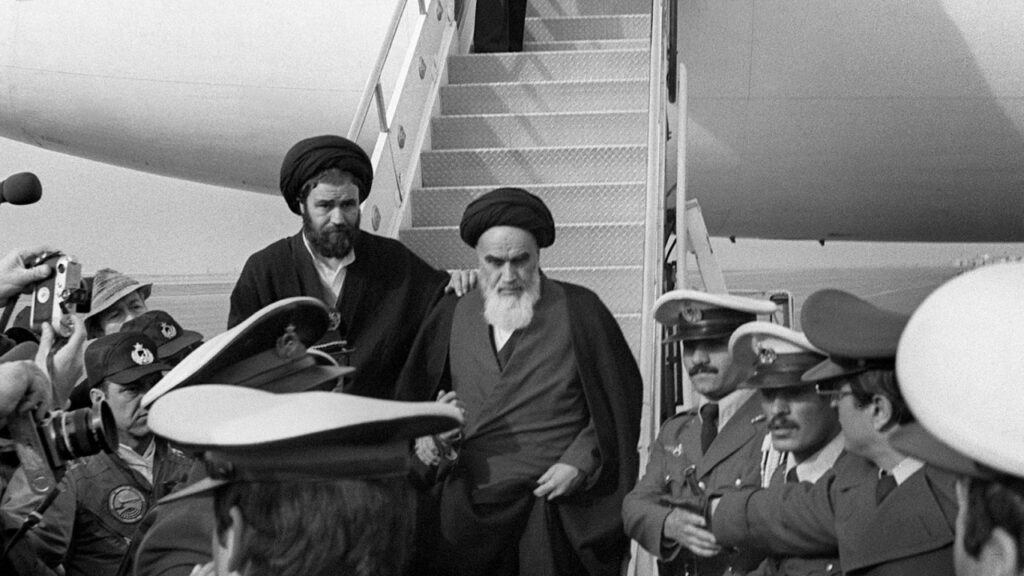

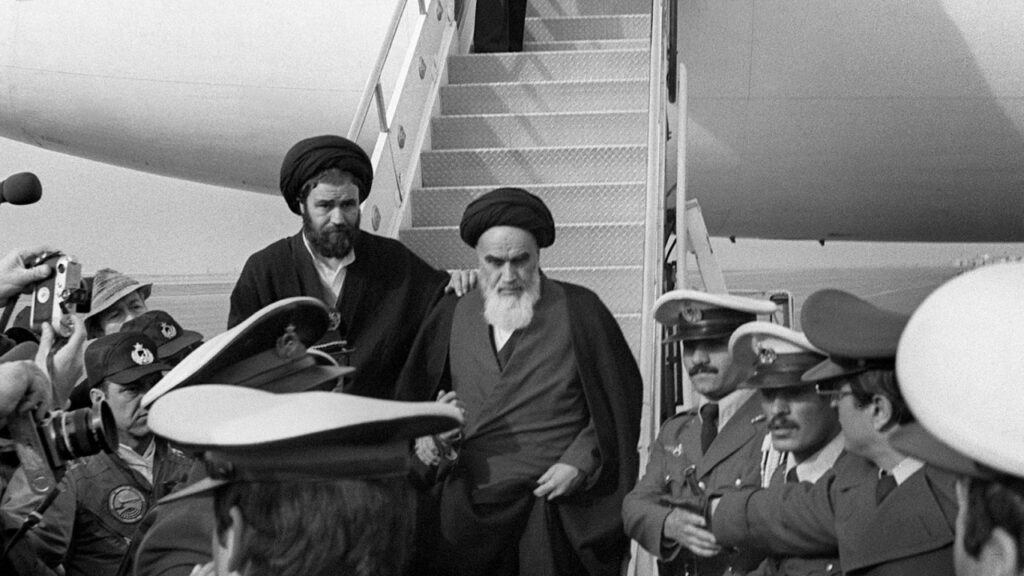

Khomeini returned from exile on February 1. The crowds that greeted Khomeini totaled more than three million, forcing him to take a helicopter from the airport to the Behest-e Zahra cemetery where he prayed to the “tens of thousands martyred for the revolution.”[20]

The new regime soon set the official figure at 60,000 but according to a study by the Martyrs’ Families Foundation, 2781 demonstrators died in the fourteen months between October 1977 and February 1979. By global and historical standards this was not a bloody revolution.

The blood would really begin to flow once the shah had left, and the revolutionaries would start to get over the spoils of a revolution that had left them in charge of one of the most powerful and important states in the Middle East. This mass movement of the Iranian people, which began as something meant to end repression, wound up entrenching it instead. [21]

The Shah was finished on February 11, when the armed forces, faced with chaos and the prospect of being ordered to fire on the public, declared that they were now “neutral” and would not defend the regime. Of the three pillars the Pahlavis had built to bolster their state, the military had been immobilized, the bureaucracy had joined the revolution, and court patronage had become a huge embarrassment.[22]

On 1 April 1979, following a rigged national referendum (98.2 percent voted in favor), Iran was declared an ‘Islamic Republic’[23] Most observers expected the clergy to withdraw from politics soon after victory. Liberal and Marxist currents within the revolutionary coalition seemed to be in a strong position to dominate a post-shah order.

Today it is often forgotten that the revolution was not originally aimed at producing an Islamic theocracy. What became the Islamic Revolution in Iran was initiated not solely by an Islamist movement but by a coalition of interest groups united against the shah. However, in every revolution, there’s such a problem: For different groups being united against a common enemy, it is clear who they don’t like and what they don’t want but it’s never clear what they actually want.

The course of events in Iran once again demonstrated that revolutions involve not only the overthrowing of a previous regime but also the selection among opposition currents that will ultimately triumph and imprint their own agendas on the revolution as a whole.[24]

The first post-revolutionary government headed by Prime Minister Mehdi Bazargan was overwhelmingly made up of lay liberal-minded Muslim nationalists but the disagreement of his cabinet with Khomeini on supporting the hostage crisis resulted in their mass resignation less than nine months after it came to office.

The Hostage crisis of November 4, 1979, was the beginning of a crisis that would provide the catalyst for decades of hostility. It all started when some 300 protesters calling themselves the “Muslim Student Followers of Imam’s Line” occupied the American Embassy in Tehran and took 63 US citizens hostage. The hostage-takers were Khomeini supporters but they acted without his knowledge. The provisional government whose members included both moderates and conservatives also didn’t know about this but they wanted to resolve the situation very quickly by saying Khomeini to make a speech to protesters to make them stop what they’re doing. But the hostage-taking proved popular on the streets of Tehran where protesters from all ideological roots united and gathered in support of the students. As Khomeini saw this picture, he was very sensitive to the opinion of the masses because he wanted to remain as the greatest person in people’s minds. So, he gave his support to the students and in giving the siege his official stamp of approval he set Iran on a collision course with the US.[25]

Abbas Milani says that if somebody tries to chronicle all the economic, political, and emotional damages that were done to Iran, as a result of the hostage crisis one would find out that it was one of the most stupid and costliest decisions made by any government.

Barzangani and his cabinet were aware of the fact that as a government, they could ask the United States to close down its embassy, ask all the personnel to leave Iran but they could not support or endorse the hostage-taking. However, Khomeini knew that one way to undermine Barzangani and undercut him was to have the hostage crisis and used this effectively.

Through a series of maneuvers over the course of two years, the liberal-minded bloc was forced out. The clergy set up a state with theocratic forms that would provide it perpetual role. Khomeini’s huge popularity, as a ‘semi-divine’ figure and a symbol of resistance against the Shah, enabled him speedily to establish a system of personal rule and out-maneuvers other opposition groups.[26]The hostages remained in Iran for 444 days until January 1981 when the Reagan administration could bring them back to the United States. The hostage crisis may have fatally damaged Iran’s reputation abroad but at home Ayatollah Khomeini was more powerful than ever.

A new theocratic constitution was adopted In December 1979, under which Khomeini was designated the Supreme Leader, presiding over a constitutional system consisting of an elected parliament and president while substantive power remained in the hands of the Shi’a religious elite.

The new government was based on the concept of velayet e-faqih, meaning the rule of the jurist. Khomeini’s notion of an Islamic republic was twofold. On the one hand, it stressed the Islamic government as the rule of divine law over the people where the sovereignty lies not with the people but with God. On the other, it called for a republic based on democratic structures. Thus, an Islamic republic, according to Khomeini, was a democratic state in its real meaning as it was based on a religion that was grounded in equality and justice.[27]

The developments in Iran showed us how an actor changed its place in the international arena completely in such a short time, and how it suddenly started to demonize its former greatest ally as the “Great Satan”.

REFERENCES

[1] Editor Lust, E. (2008). The Middle East. United States: SAGE Publications. p.811

[2]Best, A. (2015). 20. Yüzyılın Uluslararası Tarihi. Ankara: Siyasal Kitabevi. p.498

[3] Editor Lust, E. (2008). The Middle East. United States: SAGE Publications. p.811-812

[4] Heywood, A. (2018). Küresel Siyaset. Ankara: BB101. p.274

[5]Abrahamian, E. (2008). A History of Modern Iran. Cambridge University Press. iBooks, p. 457

[6] Editor Lust, E. (2008). The Middle East. United States: SAGE Publications. p.815

[7]Abrahamian, E. (2008). A History of Modern Iran. Cambridge University Press. iBooks, p.228-229

[8] Al Jazeera English (Producer). (August 2009). Iran 1979: Legacy of a Revolution [Documentary]

[9] Abrahamian, E. (2008). A History of Modern Iran. Cambridge University Press. iBooks, p.458

[10] Al Jazeera English (Producer). (August 2009). Iran 1979: Legacy of a Revolution [Documentary]

[11] Editor Lust, E. (2008). The Middle East. United States: SAGE Publications. p.819

[12] Abrahamian, E. (2008). A History of Modern Iran. Cambridge University Press. iBooks, p.458-459

[13] Editor Lust, E. (2008). The Middle East. United States: SAGE Publications. p.819

[14] Abrahamian, E. (2008). A History of Modern Iran. Cambridge University Press. iBooks, p.460-61

[15] Gündüz, T. (2016). Büyük Olayların Kısa Tarihi. İstanbul: Yeditepe Yayınevi. p.150

[16] Gündüz, T. (2016). Büyük Olayların Kısa Tarihi. İstanbul: Yeditepe Yayınevi. p.150

[17] Editor Lust, E. (2008). The Middle East. United States: SAGE Publications. p.820

[18] Abrahamian, E. (2008). A History of Modern Iran. Cambridge University Press. iBooks, p.465-466

[19] Ali Ansari, Kasım Aarabi (2019). Ideology and Iran’s Revolution: How 1979 Changed the World. Tony Blair Instıtute or Global Change. p.8

[20] Abrahamian, E. (2008). A History of Modern Iran. Cambridge University Press. iBooks, p.470-471

[21] Ali Ansari, Kasım Aarabi (2019). Ideology and Iran’s Revolution: How 1979 Changed the World. Tony Blair Instıtute or Global Change. p.9

[22] Abrahamian, E. (2008). A History of Modern Iran. Cambridge University Press. iBooks, p.473

[23] Heywood, A. (2011). Global Politics. Palgrave Foundations.

[24] Editor Lust, E. (2008). The Middle East. United States: SAGE Publications. p.821

[25] Al Jazeera English (Producer). (August 2009). Iran 1979: Legacy of a Revolution [Documentary]

[26] Editor Lust, E. (2008). The Middle East. United States: SAGE Publications. p.821

[27]Best, A. (2008). International History of the Twentieth Century and Beyond. Routledge. p.465